(Russkaya Starina, “Oborona Petropavlovskago porta.” A.P. Arbuzov. Vol. 1, 1870, Part 2, pgs. 298-313 )

The Defense of Petropavlovsk Port against an Anglo-French Squadron in 1854

(From the notes of an eyewitness and participant in this event.)

Our actions in the Amur territory and the defense of Petropavlovsk are facts of history. Since history, as Cicero expressed it, ‘must have two laws, namely: it must not dare to tell a lie, and it must not fear to tell the truth,” everyone will get what he deserves in this case, too. And, perhaps, this history will uncover some persons who now remain unknown, and persons to whom at present are ascribed, along with others, a purely executive role when in this affair they were actually independent. (Nevel'skoi. Morskoi Sbornik, 1860, Book XII, pg. 385.)

Note: It is to this same Gennadii Ivanovich Nevel’skoi that Russia is indebted for obtaining the Amur territory through the Treaty of Aikhun on 16 May 1858. In 1854 Gennadii Ivanovich blazed that route along the Amur River by which Russia’s eastern shores were defended from the Anglo-French attack and Kamchatka saved.— A.P. Arbuzov.

In the December 1854 issue of Morskoi Sbornik there was published an article “The attack on Kamchatka by an Anglo-French squadron in August 1854,” based on completely unreliable information regarding the repulse of the Anglo-French squadron’s attack on the Petropavlovsk port. Thus, details of a famous defeat of a hostile attempt on our homeland’s eastern limits was made known to Russia in an incomplete fashion, and mainly from the aforesaid article. As a participant in this event, I want to present it in a fuller and more accurate form, so I consider myself obliged to publish extracts from the notes I made at the time. I am an old seaman and soldier, and have no inclination to hone my ability to write a technical work. I am unacquainted with literary style, and I am not attracted by the author’s fame. Yet I am accustomed to respect facts and honor the truth. That is what sets me to writing a few truthful words about an event of glorious honor for the Russian sailor and soldier—simply and accurately, without literary pretensions.

Highest Order to the fleet No. 1271, dated 16 December 1853, appointed me assistant to the military governor of Kamchatka, captain of the port of Petropavlovsk, and commander of the 47th Naval Équipage. Consequently I made a winter journey to my new posting and arrived at Irkutsk in March. At the beginning of April 1854 I was at the village of Lanchenovo on the Shilka River in the Nerchinsk District. Here I encountered 500 soldiers gathered from the 12th, 13th, and 14th Siberian Battalions under the direction of Ensign Glein, who had been assigned to Sitkha along with some of the soldiers. The first thing I did here was take measures to prevent the spread of springtime fevers in the force. Then I set to instructing newly drafted personnel in military movements that I myself learned from European instructors in Turkey in 1848. Among other things, I trained in quickly forming up and maneuvering by signal horn, fencing with the bayonet against hanging ball-shaped targets fashioned from straw and grass, which during rest periods also served as pillows. For the practical use of such pillows I am indebted to the example of Polish gymnasts serving as sailors on Black Sea ships. Fortunately, it was not necessary to have marksmenship training since over half of the soldiers were originally Siberian bear hunters and proved to be masters of this art. I also won’t hide the original method by which I trained sailors to maneuver in extended order in broken terrain. I selected a hilly and woody spot, then invited village girls to stroll on over to where I had led my command. I then exercised the young soldiers in hiding behind trees, bushes, and rocks, and had them perform every kind of evolution for a soldier in extended order, thus quickly surrounding the “enemy” in a flash by signals. I had them change front in each of the extended formations and move to the attack so that not one of the “enemy” could flee and hide. With jokes and in good humor, as if in play, the wild soldiers became accustomed to fighting on land and skillfully using terrain. As for the “enemy,” after the exercise they gathering in my yard and here shared songs, rattled a drum, blew through a comb, and did not stop dancing until late at night. All this helped maintain the most jolly spirits in my command, and no thoughts of privations and dangers soon to come clouded anyone’s head.

On 3 May we began preparing a force afloat using rafts made from branches and tree trunks, six barges, twelve officer boats, and the steamship Argun. It was given to me to take the ship down the river from the Shilka factory to the upper Amur where the Shilka joined with the Argun. Not having any map or navigator, I could only undertake transporting the ship upon the commander-in-chief’s assurance that I would not be held responsible for what events might occur or any damages from underwater rocks and trees. Even so, I depended on my experience sailing the Danube in 1828, ’29, and ’30, when I learned how to determine the channel by the currents, appearance of the shore, and the turns of the river. So, on 14 May, accompanied by the ringing of the bells of the blessed holy Orthodox church of the Transfiguration of Our Lord, our steamship let herself into the current at the head of our flotilla. Our force consisted of 52 parts comprising over 1000 soldiers, 100 mounted Cossacks, a light battery, a herd of cattle, provisions, and a choir with musicians. In three days the steamer reached her goal and stopped at our furthest outlying settlement, Ust-Streletskii. Continuing onward under the leadership of Nikolai Nikolaevich Murav’ev, on 17 May we descended into the Amur, a large river flowing between islands and high banks. On 12 June we stopped at Kizi Island, less than 80 miles from the river’s mouth. After staying there for two days, I was sent to the port of de Castries with 400 soldiers by crossing Lake Kizi on the steamer Argun with boats in tow and then traversing marshes. We came there in three days and in that time covered 16 miles. During the march soldiers used stretchers to carry ammunition, provisions of rusk and groats, and the belongings of Captain-Lieutenant Karalov, Engineer Lieutenant Muravinskii, and myself. The way was very hard. In many places while crossing the marsh we had to cut down trees and branches to make bridges and crossways. In some places we had to jump from one small mound to another… The two reindeer we took with us for riding turned out to be of little use due to the ill fit of the saddles and an inability to ride, so we had to go on foot. The whole detachment was fed with salt beef, soup made from boiled wild greens, and ramson (bear’s garlic) gathered along the way. We drank brick tea usually boiled in the soldiers’ kettles. This tea is a lifesaving counter against marsh miasmas. In this manner, accompanied by a local inhabitant, a semi-savage Goldi who served as our guide, we came out onto the shores of the Tatar Strait. Although weary from the hard journey, the familiar sea atmosphere revived me, and a six-mile walk along the shore brought us to de Castries’ port. We spent the night here waiting for Murav’ev, and the next day were carried away by the transport Dvina which had come for us from Petropavlovsk.

Finally, on 19 July we set off

on the Sea of Okhotsk through the second Kurile strait. The journey through the

marshes to de Castries’ port had been hard, but our voyage by sea and ocean

threatened to be fatal. The large number of persons on board the small

transport meant very cramped conditions. During the 35-day voyage the men’s

rations were very limited, and towards the end it came to feeding them with

broken rusk sweepings and a very small amount of rainwater collected in tents

and sails spread over the upper deck. During the whole trip the men were

trained in gunnery and prepared to meet the enemy. But Providence clearly was

protecting us, since in spite of all the privations of the trip, we carried

into Petropavlovsk only three weakened men.

Note: I cannot neglect to mention with deepest

admiration the late Stepan Thedorovich Solov’ev, who donations for the

soldiers’ welfare during the Amur expedition amounted to over 15 pounds

[syvshe pol-puda] worth of gold. He was the one who provided boots for

the lower ranks, underclothes, and the brick tea that was so beneficial for

these Siberians. —A.P. Arbuzov.

On 24 July, the day of Christian martyrs, we arrived at the port of Petropavlovsk and joyfully met the 44-gun frigate Avrora. There were 350 sailors on this frigate, which was a significant reinforcement for the Kamchatka port’s garrison that had previously not exceeded 283 men together with the transport’s detachement. On that day, strictly following military discipline, I presented myself to the commander, Major General Zavoiko. However, our joy upon meeting comrades was not long lived. Upon arriving at the port after risking death from hunger along the way, here we had to face the same thing, since in accordance with the orders that had been issued, the reserves of provisions on hand were given out to the workers of the North American Company. We were only saved from perishing through starvation by the arrival from Hamburg of the clipper Sv. Magdalina with 900,000 pounds of provisions one week before the appearance of the enemy on 10 August. Besides this, it was soon apparent after our arrival at the port that there prevailed an old-fashioned and extremely strict system of control, thanks to which the magnificent deepwater sailors who made up my 47th Naval Équipage were completely ruined, becoming men who fomented trouble and thievery. The discipline in the crews was such that during the enemy siege it led to having to resort to execution by firing squad of men caught stealing (after they had already once been tied to a pillory and granted mercy). In the midst of this chaos and disorder the only hope was in the soldiers I had just brought in and the crew of the glorious frigate Avrora.

There were 983 lower ranks under arms and 30 armed civilian officials, a total of 1013 when the enemy expected to find here only a detachment of invalids, as was reported to him by whaling ships in the Sandwich Islands that had wintered in Petropavlovsk.

Upon entering into my duties regarding the port and crew, I right away noticed a shortfall in supplies as indicated by the records. I then discovered 400 yards of grey cloth hidden by adjutant K— in a loft, which my predecessor Freitag had intended to use to make warm blankets for the sailors. When what I had found out was reported to Zavoiko, instead of investigating he put my commissary official, Rudnev, in the guardhouse…

Afterwards, on 10 August, I received Order No. 1207 from Zavoiko, telling me I was to travel 500 miles [800 verst] to familiarize myself with the country as far as the village of Bolsheretsk. How unexpected and strange such an order seemed to me! But being accustomed to dutifully carrying out orders and not wanting to waste time, I hurried to inspect the defensive line and report the weak points I found to the commander. I also asked that in order to better protect the supplies brought by the clipper Sv. Magdalina—just then unloaded and placed in storehouses—that they be distributed among various huts before the frosts came in September. I anticipated that without such a distribution, bombardment of the town might at one blow deprive the garrison of absolutely irreplaceable provisions. But in reply I received Order No. 2352 of 14 August which noted a deficiency in the report I had made, claiming that the hills were so high that enemy shells would not be able to fire over them. (I do not consider it excessive to note that my assessment proved to be so accurate during the port’s bombardment that Zavoiko, on the night of 18/19 August, gave orders to move all supplies from the magazines inside the port and sink them in the lake. It was fortunate that the men worn out during the night were not needed to repulse the enemy.) Additionally, this order also reminded me I was to carry out the directive of 10 August without fail. Seeing as I could do nothing except resign myself to carrying out my duty unconditionally, I was hurrying to finish the preparations for my departure when, completely unexpectedly, important circumstances caused me to remain at my post, all in accordance with regulations…

On the evening of 16 August a

signal from the distant light towers informed us of the appearance of ships on

the Eastern Ocean’s horizon, which to everyone’s mind meant the arrival of

the enemy. This supposition was confirmed on the following day. On the morning

of 17 August a three-masted side-wheel steamer entered Avacha Bay under an

American flag. The ship was immediately recognized by officers of the frigate

Aurora as she had been with the squadron they had encountered in South

America, at the port of Calao. There were few persons to be seen on the

steamship and she remained about a mile from the port’s advanced

fortifications. A navigation officer, Ensign Samokhvalov, was sent in a

whaleboat to meet her and offer services to guide her into port. But when the

steamship noticed the small sloop, she immediately turned back, and at this

time many persons could be seen on her deck. It was then clear that the

squadron cruising at the bay’s entrance belonged to the enemy. The next day,

the 18th, the squadron entered Avacha Bay with a southeast wind. It consisted

of English ships: frigate President under Admiral Price’s flag, 52

guns; Pique, 44 guns; three-masted steamship Virago, 8 mortars;

French ships: frigate La Forte under Admiral Febvrier-Despointes’

flag, 60 guns; Euridice, 32 guns, and the brig Obligado, 18 guns.

Note: All dates given by me were checked with the

logbook of the frigate Avrora, located in the Navy Ministry’s

archives, but they do not agree with the dates given in the 1854 Morskoi

Sbornik article.—A.P. Arbuzov.

Under such exceptional circumstances, I adhered to the strict sense of military regulations and had no right to leave my post while in view of a menacing foe. The regulation states that no serving personnel in the execution of their duties may take heed of any person or use any pretext, but are obliged to carry out their duties strictly as stipulated. The regulations further state that a commander’s senior deputy does not leave his post in the case of the commander’s death; that an officer commanding a small unit cannot be sent anywhere for longer than three days, and that the captain of a port may not leave his post, under the penalty of death… When I met Zavoiko at the port on 18 August, before any enemy action, I explained to him all these circumstances in the presence of the frigate commander, Captain-Lieutenant Izylmetev. But in reply to this Zavoiko declared that he was acting according to special instructions. I then told him, “If your authority is greater than the regulations, then put me in irons and throw me into the guardhouse!” At this Zavoiko turned away from me and relieved me of all my duties, which he announced that day in a general order. Seeing that there was nothing left to do except offer myself as a volunteer, I requested that favor from the commander of the frigate Avrora. He agreed, so I was not to be a mere spectator in the business about to begin.

From the frigate, we soon spied the enemy landing being made in rowboats at Krasnyi Yar, at the outlying Battery No. 4. The enemy landing went in under the cover of smoke from his firing on Battery No. 1, which he called the Shakhov Battery, on the cape below the inner light tower above the limestone cliff, and from cannon fire on Battery No. 2 located on the spit popularly called the Koshka [“Little Spit”] and which formed one side of the bay. This bay was closed by a boom and covered by the port side of our frigate Avrora. On board the frigate I managed the guns at the captain’s cabin. Observing the flight of the shot, I ordered that a gun be elevated to maximum and fire an aimed round. The shot fell into Battery No. 4—already occupied by the enemy who had hoisted the French flag—at the same time as that battery’s commander, Midshipman Popov, having seen no reinforcements, spiked the guns and left with the powder and rounds. In the meantime our groups of marksmen began to be gather, and in spite of their disorder as they formed a crowd near the frigate without any overall direction, the enemy saw them as an unexpected massing of our forces and immediately retired. During this they pushed one gun out of the battery and damaged the rope and tackle of the naval carriages. Now Zavoiko came up to us on the frigate, accompanied by his executioner with cased whips… This lowering of a commander’s dignity so struck me that, being already weak after the trip on the transport Dvina and subsequent events, I fell into a faint at the battery, from where I was carried unconscious to the orlop deck where with the doctor’s helpI came to. Here I found out that Zavoiko had left and ordered the batteries’ guns to be spiked and, if the frigate did not withstand the enemy’s firing, it—along with the transport Dvina lying alongside—was to be burnt, and the crew collected on shore. Hardly able to keep on my feet, I went to the captain’s cabin where I met the frigate’s chaplain, hieromonach Father Ion, and told him, “Father, maybe I’m going to die soon, but my final declaration is that our duty is to unspike the guns and recover the situation!” (This respected hieromonach displayed great courage during the fighting; from the very start of the battle he remained at the railing or in the shrouds, encouraging the sailors and coolly counting how many rounds flew by.) After these words I went into the cabin and told the frigate’s captain and officers that Zavoiko’s rash decision to spike the guns would lead to no good, and so before anything else it was necessary to unspike them. In reply to my call to remove the spikes, Izylmetev fully agreed that such action was imperative and promised to entrust it to artillery ensign Mozhaiskii.

After this I noticed that the crew manning Battery No. 1 had to suffer from fragments from the cliff which had already wounded the battery commander, Lieutenant Gavrilov, in the head. I asked Izylmetev to arrange for an old topsail to be hung over the battery’s cliff, which was done the following day. By the commander’s order as relayed through the frigate’s cadet, during this time all battery guns were spiked, except in Battery No. 2 on the spit and covering the frigate, whose commander understood how wrong that decision was. Fortunately for us, due to the lack of steel in the port the barbed spikes were made from soft metal nails. On the morning of the 18th we fired the guns by touching them off from the mouth and the powder’s explosive gas forced the spikes out from the touchholes. The personnel who unspiked the guns told me that when carrying out this firing they almost sank one of the enemy landing boats. Meanwhile, at a signal the enemy withdrew and his firing ceased, as if for rest after a test in exchanging shots.

From 4 p.m. on the 18th

through the whole of the 19th we were busy repairing damage, as was the enemy.

Among the damage we noted that the President’s stern and stern transom

were smashed. In all probability it was during this that Admiral Price was

killed by Battery No 1. On can assume that once Price came into position he

went down to his cabin. Our shell crashing in caused a jolt which brought the

captain to the cabin where he found the remains of the admiral. He ordered a

servant to cover them and himself declared to the crew that a shot passing

through harmlessly was no cause for alarm, and that it was more appropriate now

to be more accurate in laying guns onto the enemy. This necessary lie on the

spur of the moment led to taking advantage of Admiral Price’s glorious death

and making up that it was suicide, supposedly committed by the admiral because

he was old and weak in energy, and feared taking responsibility for delay and

the failure of the first attempt to capture the port and Kamchatka. Shame on

these slanderers! It is ridiculous to believe such liars when they say that a

Russian shot or shell could not kill an English admiral… It is all the more

strange to doubt since the commander of Battery No. 1 told me, and this was

known to all, that when the battery first test fired into a target, its first

volley smashed it into chips. And when the current brought a frigate’s stern

toward the battery, our boys aimed true and smashed it.

See Morskoi Sbornik, September, 1855,

“Physical and moral courage,” translated from English. In this article it

was presented, among other things, that “Admiral Price was more afraid of

responsibility than a child is of a ghost.” But Price was distinguished from

his youth for his fearlessness. Once, as a midshipman, he climbed to the very

top of St. Paul’s in London and hung a handkerchief there, daring anyone to

volunteer to take it down, but no other similar deeds of his have been

found.—A.P. Arbuzov.

On the 19th the admiral’s body was buried on the shore of the Bay of Tatary, and above the grave a mound was raised and covered with turf. When time soothes passions, the English will undoubtedly honor the memory of the fallen warrior with a fitting mausoleum erected over the grave of the slain admiral!

On 20 August the enemy opened fire from their ships from the same positions but at closer range, calculating that destroying the port’s batteries would be a decisive act, based on their superiority in artillery. But our sailors became used to being under fire and persistently repaid the enemy in kind, so that on this day the foe was unable to realize his expectations. Our success would have been even greater if the commanders of our batteries had used red hot shot, for which shot heating stoves had been built out of pig iron ballast in Nos. 2 and 3 (like the stoves used by our Black Sea sailors for their saunas). Tongs were made and brought from the frigate to shore. Wads were wetted All that was lacking was some ability! When I asked the commander of Battery No. 2, “Why don’t you fire hot shot?” I received the simple- hearted reply, “Strange that you suggest that when you see that I have to fire by ricochets; the shot would get cold from the spray!...” Hearing such nonsense, I nonetheless had to remain silent because by direction of Zavoiko I was deprived of the authority to give orders. Finally, after being fully convinced just how badly arrangements had been made for the defense, I considered it a soldier’s duty to set aside personal feelings of being insulted and turned to Zavoiko to offer my services in the defense of the port. To this end I sent him a letter in which I declared that I had been in action against the enemy over twenty times and therefore there was scarcely an officer present who could surpass me in combat experience. In answer to my letter I was given permission. The order for this was given on the morning of 23 August. Upon taking command of my unit, I began by gathering all personnel and in a short and encouraging speech reminded them of their responsibilities. I also brought up their indecision during the call to arms to repulse the enemy on 18 August. “Now, friends, I am with you,” I added, “and I swear by this cross of St. George which I wear with honor for 14 years now, that I will not disgrace my name as commander! If you ever see any cowardice in me, then stab me with your bayonets and spit on the corpse! –But know that I demand absolute obedience to this oath—to fight to the last drop of blood!”

“We will die rather than step back!” was their answer in one voice.

“Singers to the front!” I cried, enthused in spite of myself. And the soldier cheerfully and bravely brayed the hymn: “For the tsar, for Rus the blessed we roar the song in the fated hour!” I dispersed the men and then ordered that bayonets be sharpened and flints and firelocks checked.

On the 19th, as the English

were conducting the funeral for Admiral Price, they met two American sailors

from the vessel in our harbor under their national flag. These sailors had been

sent by their skipper to chop wood, and out of feelings of empathy for their

race they took it upon themselves to show the English a path suitable, in their

opinion, for entering and seizing the port.

Thus acted Americans, but here is how a Russian

tar conducted himself in a similar circumstance: On the 18th, after the first

affair, one of our boats came obliviously into the roads from our brick works.

In it were Boatswain Usov with his wife and two children and three oarsmen. The

port authorities were so negligent that they had not notified the works not to

enter the roads because of the appearance of the enemy. Our jacks

sitting in the rowboat took the enemy’s firing for salutes and calmly rowed

up to the ships. The boat was immediately captured. In 1855 one of these

captured sailors of the 47th Équipage, Semen Udalov, threw himself overboard

from the enemy brig Obligado rather than serve them against his own

countrymen when in that year the enemy squadron once again moved against the

port. It is fitting to note that the first person to report this Russian

sailor’s act was a foreign officer from the brig Obligado, Ed. Du

Hailly (Revue des deux mondes, Vol. XVII, Issue I, pgs. 169-198). In

Morskoi Sbornik (1857, Book VII, miscellaneous notes, pgs. 4-7) there

was placed the same story from Semen Udalov’s own comrades: they were with

him in captivity and saw how he refused to go to a cannon when called upon by

the French commander, as he did not want to fire on his own side, and with a

farewell cry to his brothers to not raise their arms against Russians, he flung

himself from the shrouds into the sea. —Ed.)

Subsequently, at about 8 o’clock in the morning on 24 August the foe decided to make use of this discovery, and in order to mask their attack they began bombarding Battery No. 1 on Cape Shakhov where the sail was hung out, Battery No. 3 at the La Perouse neck, where the commander, Prince Aleksandr Maksyutov, had his arm torn off, and Battery No. 7 at the end of Nikolskaya hill. Then they disembarked a landing force and peppered the frigate with bullets without causing any harm. Having overthrown batteries No. 3 and No. 7, the enemy landed a full-strength party of 700 men. When I heard the alarm I rushed to the barracks and saw everyone was in motion. I approached Zavoiko, who during the whole action stood behind the powder magazine under the hill. Here I noticed the mortally wounded son of the merchant Sakharov. He was still breathing and I arranged for him to be taken to the hospital. I saw that our civilian officials armed with muskets and bayonets were completely uselessly while deployed around the foot of the hill to the right of the magazine and were exposed to enemy fire. I obtained permission to immediately draw them back and position them as bodyguards around the commander… To show how chaotically the beginning of the battle was conducted, I point out what occurred next to Zavoiko himself. The police chief, Lieutenant G***, having been ordered to the heights of the Nikolskaya hill and battery No. 7, inaccessible by sea, on his own descended from there with his marksmen when he saw how the enemy was coming around him using the above-mentioned path, not at all understanding that Battery No. 6 with six guns was able to defend that route. Then, as if he wanted to justify himself, he sat down at Zavoiko’s feet and fired at chance targets, crying, “Got one, got one, your excellency!” The scene was truly comical!...

At this time the French foe under the leadership of the English Lieutenant Parker appeared halfway up the hill. In response to this two parties of marksmen were sent out, the first under the command of Midshipman Mikhailov, and the second under Lieutenant Ankudinov. (In Mikhailov’s party a soldier from the Siberian battalion, Suntsov, crawled forward from the hill and shot Lieutenant Parker through the head, the bullet entering under the chin and into the skull.) During this time I followed the enemy’s movements while smoking a cigar and conversing with engineer Lieutenant Muravinskii, when suddenly a bullet hit him in the leg, and another killed outright a horse standing about 600 paces from us next to a field gun. Meanwhile Zavoiko, who had found out about the enemy movement around the hill, ordered me to go to Battery No. 6 at the lake, about 200 paces from the powder magazine, and make sure they did not pass down the path that had been shown to them. On arriving, I asked the battery commander, Gozekhus, to have the crew of clerks to alternately load the guns with solid shot and canister, and myself ordered the cossacks standing there to use their swords to cut grass to cover up the guns. When with the help of Ensign Sakharov of the marine artillery all the guns were aimed and sited, and the voluble clerks placed behind the rampart, I took up a position standing on the banquette. Soon two Englishmen in red uniforms and white cross straps appeared. Behind them came four more who thought to aim at me, being the only live target. I stood 600 paces from them, between the first and second guns from the left, and being at that time in simple ignorance of the range of rifle bullets, I just threatened them with my saber, saving the charges in the guns. During this time the rest of the disembarked Englishmen set fire to the warehouse holding supplies of cut-up salt fish. The enemy soldiers joked at my expense but did not attempt to shoot, and then made as if to turn back. I then pulled the cord to let off a cannon shot, and the enemy hid behind the fish shed, dragging one of their number by the arms. Seeing that there was no further use for my presence at this place, I turned over my post to the commander, ship’s engineer Gozekhus, and went to report to Zavoiko.

While on my way I noticed that the enemy was spread over the hill among the short cedar bushes and open areas. Thereupon I asked to personally lead a party of thirty marksmen. The general responded that he could not order this as he did not have the personnel near at hand. I repeated my request and added, “Around your excellency are still loyal officials, and if the enemy recovers himself and comes back, then our parties will be placed between two fires—from the rear and the front.” Secretary Lokhvitskii, standing alongside, supported my view, and I received permission to go about this business. I set off with my party to outflank the enemy behind the magazine and almost shot non-commissioned officer Shepelikhin, taking his dark-blue forage cap in the bushes for the enemy’s. Going further, I met Midshipman Fesun with twelve sailors. The midshipman did not accept my suggestion to join with me; he was hurrying to Zavoiko, his uncle. Then, going onward, I saw a French cadet who had been bayoneted by a Russian soldier, and then Lieutenant Pilkin, Ensign Zhilkin, and the boatswain Podsamuilov, with 90 sailors. They had all been called from the frigate by a naval cadet sent by the commander with the summons: “Everything has fallen through! Send everyone able to carry a musket!”…

I will not describe all the adventures of my party’s encounter with the enemy. After a general “Ura!” we hit the foe in the flank with the bayonet and sent them flying. Swiftly pursuing them, we soon joined up with our first and second parties of marksmen. Our success was total! We found 32 enemy bodies around the place where our parties met, of which not one did not have wounds attributable to our fine ability with the bayonet. The fleeing enemy practically threw themselves from the steep cliffs and gathered together on the shore at their rowboats. (Here, among other persons, we found afterwards a French sailor senseless from fright, Pierre Landoirs from the frigate Laforte.) At this time 16 Kamchadal natives crept up from behind the rocks, and being accustomed to shooting beaver in the head so as not to spoil the skins, they now increased the enemy losses by their accurate sniping. Enthused by the complete success of the affair, I suggested to Pilkin that we rush forward together and cut off the enemy from the rowboats. But he said he did not have any orders to do so, and after helping us he was obliged to return to the frigate, where the allies were covering the attack.

A half hour after the enemy

left, I sent a non-commissioned officer to Zavoiko with a report of what

happened, and if he ordered the retreat to be sounded we would come down the

hill. The retreat was soon heard and we returned to the magazine. Here it

pleased the general to assign me to collect the dead and wounded lying about

the hill. But I was affected by over excitement after the realization of our

success in battle and went to the hospital, where Doctor Linchevskii, to his

own surprise, had to bleed me. On returning to the magazine I was present at

the interments of both our own and the enemy’s dead. On the shirt of the

slain English leader we found the inscription “Parker,” and in a

pocket—the organization of the landing force, and an advertisement from the

Francisco theater in California for the opera Ernani with a penciled

note: “N’oubliez pas de prendre dix pairs de bracelets.” Afterwards there

was a banquet for the commander, but I excused myself and dined for the last

time in the joint mess shared by the officers and officials at the governor’s

chancellery.

Note: Since I am sworn to strictly adhere to only

the truth I do not hide the following fact, the reliability of which, along

with everything else I wrote, can be affirmed by many eyewitnesses (the names

of whom are recorded in my story). After the battle an English flag was sent as

a trophy to St. Petersburg with elaborate ceremony, being supposedly taken from

the hands of the enemy. But alas! No one ever saw this flag held by enemy

hands, no one seized it in the heat of battle. The English simply forgot

it on shore, and the deft police chief G***, when there was no enemy presence

left at all, picked up the flag and presented it to Zavoiko in the guise of a

trophy. One more word: after dinner together on 24 August 1854, all the

officials and officers who had taken part in the port’s defense offered to

give me a signed attestation that saving the port was due to no other

person—only me, Arbuzov. But I declined this honor and only asked that if

necessary they would confirm what they now said sometime in the future, by

oath.—A.P. Arbuzov.

On the 26th the enemy squadron sailed to sea.

On 3 September, in spite of my poor health, I was obliged to leave on Boat No. 1 (a forty footer), in accordance with Rear-Admiral Zavoiko’s order No. 2397 of 1 September 1854, and a second directive No. 2408 of 2 September. This was in order to deliver a supply of Kamchatka coal to the steam schooner Vostok, and then go onward to Bosheretsk. The coal loaded on the boat was wet so that we would have burned up when it began to decay. Fortunately, contrary winds di not allow us to leave for sea for three days and the tender Kadyak arrived with the news that the schooner Vostok was not at Bolsheretsk. Therefore my sentence to certain death was suspended, and soon, on the 15th, I was sent to Ayan on the hired American brig Noble.

Rear-Admiral A. P. Arbuzov

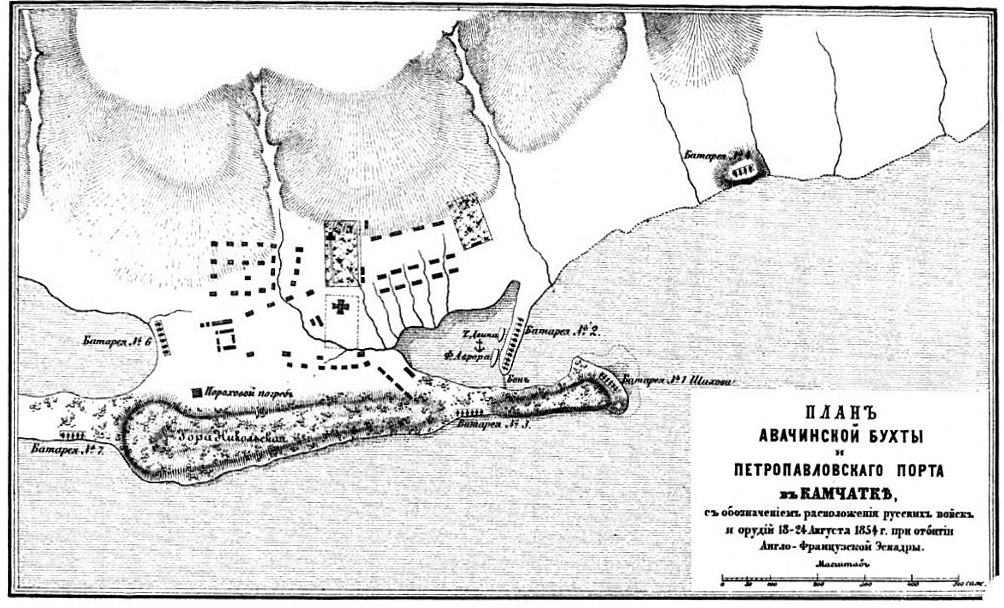

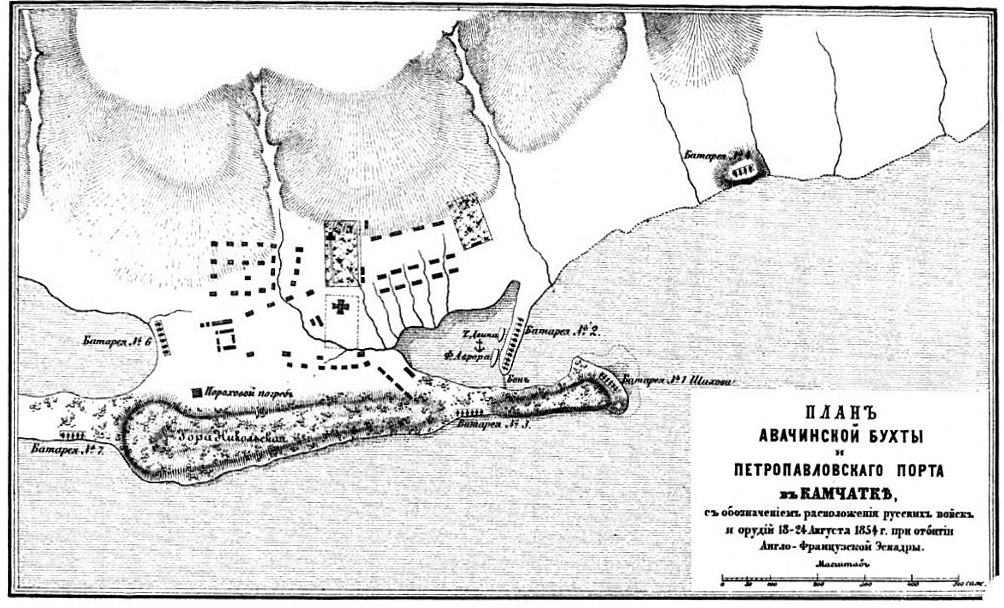

Note: In order to clarify A.P. Arbuzov’s description of the repulse of the Anglo-French squadron and its landing force from Petropavlovsk port, we decided it was necessary to add a plan of the port showing the layout of houses, batteries, the number of guns in them, and also the attacking enemy vessels. We also consider it appropriate here to explain some of the map. The Avacha bay in Kamchatka is at latitude 53° north and longitude 176° 24’ east. The bay forms a superlative sheltered basin ten miles in diameter. The largest fleet in the world could hide in this excellent roads. The inlet joins the Pacific Ocean by a passage on the south side. Upon entering through the passage we, on the east shore, meet the small port of Petropavlovsk. This is nothing more than a dead end street open to the south, 1311 yards long and averaging 432 yards wide. From the west the port is closed by a long and narrow peninsula, about 230 yards long and an average of 77 yards wide. From the southeast a spit stretches out—from 33 to 37 yards wide, and only a few feet above sea level. Nevertheless, it forms a bay. Finally, a narrow boom bars passage between the spit and peninsula. Thus nature herself made the bay a stronger fortress than anything the most skilled engineers could construct. Here behind the spit on the day of battle were positioned the Russian frigate Avrora and transport Dvina, the first of 44 guns and the latter of 12. During high tide the 11 guns of Battery No. 2 were four feet above water. Additionally, the expanse of water in front of the bay was defended by two more batteries: Shakhov’s No. 1 with 6 guns, and No. 4 on Krasnyi Yar, 5 guns. Further to the north at the foot of Nikolskaya hill was Battery No. 7 with 5 guns, and finally at the lake within the port behind the hill was located Battery No. 6 with 6 guns. ― Ed.